OFF THE WALL

Though it’s grown considerably over the past nine years, the 24 Hours of Horseshoe Hell climbing competition has remained faithful to its roots—and it’s still one heck of a party

It’s 11 o’clock in the morning, and a rebel yell is echoing off the canyon walls loud enough to encourage some skittish birds to flee their trees for the safety of the open air. And they’re not the only ones taking flight. All around me and all around this sandstone-ringed valley just outside Jasper, men and women, young and old, are climbing.

They are stuffing whole fists into cracks in the sandstone cliffs. They are stuffing calloused hands into chalk sacks for that extra bit of grip. They are pinching minuscule outcroppings of rock between fingers and thumb. They are clipping rainbow-hued ropes into bolts sunk deep into the rock (or bypassing them entirely). They are hanging upside down. They are costumed. They are bare-chested. They are slipping. They are falling. They are caught midair as their partners lock down the ropes. And every hour on the hour for the next 23 hours, they’ll scream, they’ll hoot and they’ll holler to mark the passage of time.

THE LAY OF THE LAND

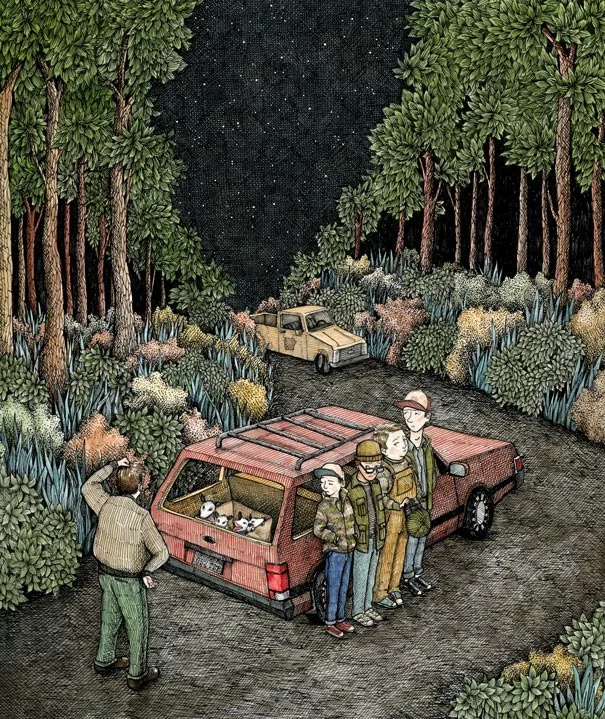

Out in the Arkansas Delta, change is coming. Thanks to a government program and a cadre of passionate landowners and hunters, trees are being planting instead of rice, land is being sloped instead of flattened, flood waters embraced instead of fought. In short: the wetlands are returning

"Bring a pair of boots—and maybe a pistol."

That’s how Charles Gairhan ends our first phone call. We’re meeting up out in the Delta at his hunting club, Cocoa Slough, and I spend the whole drive along Interstate 40 to Palestine wondering if he was kidding. I am, after all, only writing a story about wetland restoration.

But as soon as I meet him, I can tell he wasn’t. Dressed in a Fayettechill T-shirt and a camo Riceland ball cap, Charles, a 50-year-old Memphis anesthesiologist and Jonesboro native, is about as Arkansan as they come.

“Chain-sawing out here alone is not the brightest thing I have ever done,” he says with a laugh as he shows me his truck bed of freshly cut firewood. And he isn’t just talking about the potential for an accident with the power tool. There are feral hogs—some pushing 300 pounds—all over this part of the state, and he and the three other members of the hunting club are sure there’s a mountain lion and even a bear that prowl up and down the L’Anguille River, which borders their property. Hence the pistol on his hip and the 12-gauge between us in the ATV side-by-side we’re using to tour the property.

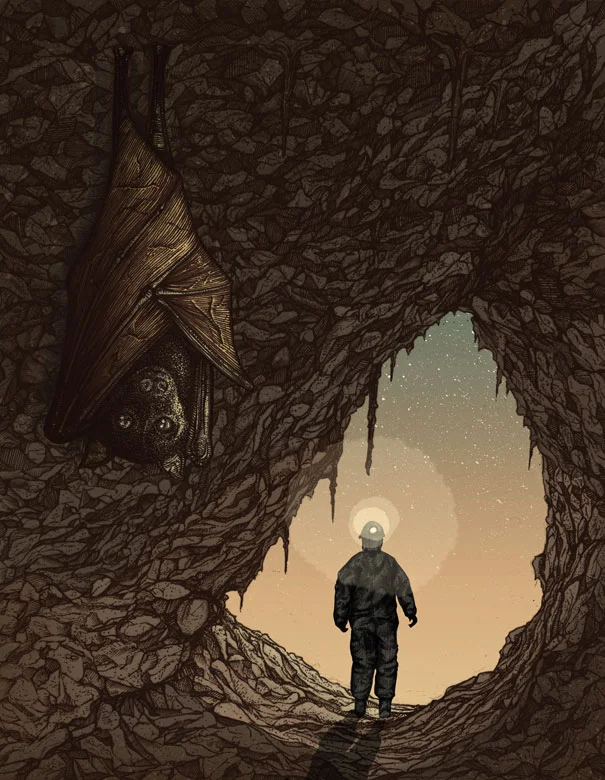

A KILLER IN THE DARK

The race to save Arkansas' bats from the deadly white-nose syndrome sweeping across the country

It’s late in the afternoon by the time Ron Redman, Patrick Moore and Daniel Istvanko begin their third cave survey of the day on Jan. 11. There is nothing special about the cave itself. It’s not pretty. There are no vaulted cathedral ceilings, no slender stalactites and stalagmites. If it weren’t for the 100 or so endangered bats living inside that the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission needs counted, there would really be no reason for these three to be there. But in less than 15 minutes, a discovery will be made that will make it arguably the most important cave in The Natural State. Unknown to anyone, a killer has struck.

The three surveyors suit up in white Tyvek coveralls and check their gear. The entrance to the cave is steep, and Redman, a 22-year veteran of the state’s endangered-bats surveying program, warns his young companions—both grad students in their first full season of counting bats for the Game and Fish Commission—that they’ll need to look down, so they’d better have their headlamps cinched tight. He has seen many a light take a tumble in this cave. Then they head into the darkness.

TIE ONE ON

Fly tying is perhaps the ultimate illustration of art imitating life—and in Arkansas, it has a life of its own

Bob Cheatham is an artist of feathers and thread. Taken in the abstract, his creations could hang on gallery walls in New York or stand in sculpture gardens in San Francisco. But don’t be fooled. Despite their fine lines and lurid colors, despite the skill and creativity it takes to craft them, these creations are tools to be used for—of all things—catching fish.

In Arkansas, as in the rest of the world, flies are a means to an end. But for Cheatham and many of the state’s fly fishermen, crafting them is a calling unto itself, one that combines a passion for creative expression with a long-held desire to catch the “The Big One.”

For Cheatham, that desire stretches back decades. Though he’s now 72, as we bounce around his Jacksonville home, it’s easy to see the boy who grew up wading across the east Arkansas Delta with a fly rod, hunting for bream. We stop to look at everything—from his antique bamboo fly rods to a contraption he built for making his own fishing lines. One moment he has me standing on his front lawn during a light June rain learning how to cast a monstrous 13-foot-long, two-handed fly rod, and the next, we’re back inside gathered around one of his two fly-tying stations as he whips up this-or-that fly like it’s nothing.

TELLING TAILS

From chasing outlaws to baby-sitting snapping turtles, game wardens have plenty of yarns to tell about taming the Arkansas wild

I was chasing them down the river in complete darkness. The guy on the front of the boat had a spotlight in my eyes trying to blind me. And I had the light on them. The guy running the motor, well, I knew who he was, and he had a reputation for carrying a pistol in his pocket. And I could see he was grabbing for something. I’m also a big baseball fan, and not long before this happened some Cleveland Indian baseball players had run a boat under a boat dock, and it killed two or three of them. I was like, “I’ve got to put a stop to this.” So I pulled my pistol out and shot his motor. Well, that ended that chase.

I wrote them a $1,000 ticket apiece for shocking fish and a $1,000 ticket for fleeing, and I took their boat and their truck. Well, they filed a lawsuit, and Game and Fish gave them their stuff back and suspended me for 30 days for shooting the motor.